The past year brought C2SMART more growth, progress, and partnership-building...

Read MoreThis post comes from Nick Hudanich, an undergraduate pursuing a B.S. in Civil Engineering from NYU Tandon.

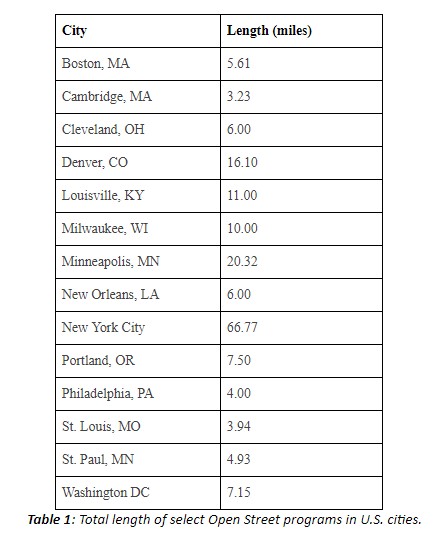

The total length of Open Streets between US Cities varies, with the updated totals as of August 2020 for major US cities being shown in table 1.

Despite New York City’s intention to open 100 miles of streets for pedestrians, recreation, and dining space (NYCOpen Streets) this summer, motorists are rapidly re-claiming roadways: citizen groups have petitioned City Hall to remove several Open Streets, ineffective police barricades have been destroyed, and street closures have remained unenforced. As Streetsblog reporter Sasha Aickin found, when surveying 112 blocks of designated Open Streets, 57% were not closed to traffic at all. Many of the rest were blocked off with NYPD sawhorses, which in several cases have been destroyed, moved aside, or disregarded, with cars still parking and traveling on the roadway.

Furthermore, the Open Streets Coalition, as The Indypendent reports, found that nearly 70% of Open Streets that were located in predominantly white neighborhoods were being effectively enforced, compared to only 12% in non-predominantly white neighborhoods, highlighting a fundamental racial divide in their implementation. The distribution of the New York Open Streets network has been disproportionately allocated to higher-income neighborhoods: Currently, The Bronx only has 3 Open Streets segments, while Queens has 6, Brooklyn has 13, and Manhattan has 39, and the median income of residents on served streets in Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens is 50%, 60%, and 20% more than the borough’s median income, respectively.

Another issue with New York’s Open Streets plan is the lack of interconnectivity and the short lengths of segments. Many Open Streets are only a single block long, with the average length of one segment being 0.22 miles. Roughly 18 miles of the total 67 miles of Open Streets (27%) are located adjacent to or within already existing parks and green spaces. Despite each borough having small clusters of Open Streets, they are rarely connected and often require traveling on vehicular roadways to travel from one to the next. Frequently, these roads do not have safe cycling infrastructure such as protected bike lanes.

The two NYC Open Streets most frequently cited as successful, Berry Street in Williamsburg and 34th Avenue in Jackson Heights, are longer than one mile continuously and are relatively well-enforced. 34th Avenue also is one of the widest Open Streets, adding almost 60 feet of open space, including a grassy median. The activity on these streets signal that there is a community desire for Open Streets to be interconnected, lengthier, and contiguous. In order to capitalize on community interest to build a connected and effective network of Open Streets, the New York City DOT should first ensure that the implementation and enforcement of current Open Streets are improved. NYCDOT should increase enforcement of all existing Open Streets, implement more permanent and durable barriers, and take action against police precincts using Open Streets as storage. NYCDOT should work on extending existing Open Streets so that they are continuous and interconnected with one another as much as possible. Finally, NYCDOT should seek to implement an additional set of Open Streets, particularly in low-income neighborhoods and areas of high diversity.

Sources

“Open Streets.” NYC DOT – Open Streets, www1.nyc.gov/html/dot/html/pedestrians/openstreets.shtml.

Aickin, Sasha. “Op-Ed: ‘Open Streets’ Isn’t Working for All of the People.” Streetsblog New York City, 7 July 2020, nyc.streetsblog.org/2020/07/07/op-ed-open-streets-isnt-working-for-all-of-the-people/.

Kuntzman, Gersh. “Council to De Blasio: ‘Open Streets’ Are NOT an NYPD Enforcement Issue.” Streetsblog New York City, 27 Apr. 2020, nyc.streetsblog.org/2020/04/26/council-to-de-blasio-open-streets-are-not-an-nypd-enforcement-issue/.

Cruz, David. “Open Streets Program Rife With Little Enforcement And Many Broken Barricades.” Gothamist, Gothamist, 21 June 2020, gothamist.com/news/open-streets-program-rife-little-enforcement-and-broken-barricades.

Klein, Carrie. “Open Streets for All: NYC’s Transit Future Is Up for Grabs.” The Indypendent, 12 June 2020, indypendent.org/2020/06/open-streets-for-all-nycs-transit-future-is-up-for-grabs/.

Gannon, Devin. “21 More Locations Open for Outdoor Dining in NYC.” 6sqft, 17 Aug. 2020, www.6sqft.com/nyc-open-streets-outdoor-dining-summer/.

“Open Streets Progress Report.” Transportation Alternatives, 2020, www.transalt.org/open-streets-progress-report.

About the author: Nicholas Hudanich is a sophomore undergraduate at New York University, pursuing a major in Civil Engineering with a Transportation minor. Nick is a researcher and a part of the website/communications team at C2SMART. Nick has contributed to transit research projects such as the MTA Jay Street Accessible Stations Pilot, and the monthly COVID-19 Blog Posts. Nick is a transportation enthusiast with a goal of visiting as many subway stations as possible, and in his free time enjoys Geocaching, a GPS-coordinate-based global treasure hunt.

About the author: Nicholas Hudanich is a sophomore undergraduate at New York University, pursuing a major in Civil Engineering with a Transportation minor. Nick is a researcher and a part of the website/communications team at C2SMART. Nick has contributed to transit research projects such as the MTA Jay Street Accessible Stations Pilot, and the monthly COVID-19 Blog Posts. Nick is a transportation enthusiast with a goal of visiting as many subway stations as possible, and in his free time enjoys Geocaching, a GPS-coordinate-based global treasure hunt.

Related Posts

C2SMARTER FDNY Collaboration Included in Popular Science’s 50 Greatest Innovations of 2024

December 9, 2024 The AI-reinforced Digital Twin focused C2SMARTER project,...

Read MoreC2SMARTER at TRB 2025

The Transportation Research Board (TRB) 102nd Annual Meeting was held...

Read MoreC2SMARTER Announces 2024-2025 Research Agenda

In 2025, C2SMARTER is focused on reducing congestion and ensuring...

Read MoreShare

Related Posts

Annual Report 2023-2024

The past year brought C2SMART more growth, progress, and partnership-building...

Read MoreC2SMARTER FDNY Collaboration Included in Popular Science’s 50 Greatest Innovations of 2024

December 9, 2024 The AI-reinforced Digital Twin focused C2SMARTER project,...

Read MoreC2SMARTER at TRB 2025

The Transportation Research Board (TRB) 102nd Annual Meeting was held...

Read MoreC2SMARTER Announces 2024-2025 Research Agenda

In 2025, C2SMARTER is focused on reducing congestion and ensuring...

Read More